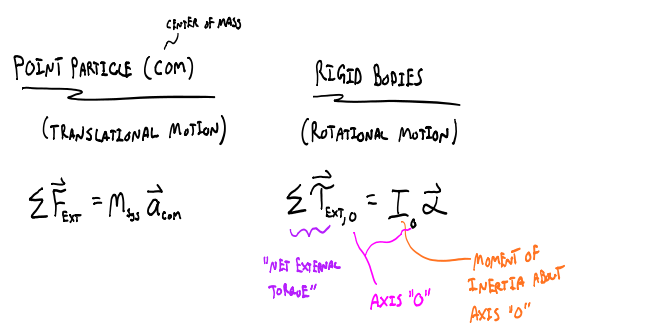

We have previously studied Newton's laws of motion while only considering what happens to the center-of-mass (COM) of an object, otherwise known as a point particle model. In statics and dynamics, we still work under the framework of Newton's laws of motion, but we extend our consideration from the point particle model to also include the shape and size of the object. The sum of the forces on a object still determine the translational motion of it's COM, but where those forces are applied will tell us something about how and if the object rotates. To understand Newton's 2nd law for rotation, we have to be able to calculate torque. Torque is similar to forces but it depends not only on the force applied, but where it is applied relative to the axis of rotation.

This very short clip shows the idea of calculating torque for a wrench when the force is applied perpendicular to the wrench.

Pre-lecture Study Resources

Watch the pre-lecture videos and read through the OpenStax text before doing the pre-lecture homework or attending class.

BoxSand Introduction

Rotational Mechanics | Torque and Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation

Torque

At first we studied how to describe the linear motion of objects with the quantities: position, velocity, and acceleration. Then we studied the cause of linear motion as described by Newton's laws of motion. At this point we have even looked at how to describe the motion of objects that are rotating by using the quantities: angular position, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. Now we will begin to develop a model for why objects rotate or not.

It should be no surprise to you that a force must be applied to an object in order to get the object to start rotating. However, the location of the applied force, and the angle of the applied force also play a role in how fast the object begins to rotate. You are probably an expert at this concept already, what is the easiest way to open a door? Do you push further or closer away from the hinge, perpendicular to the door or parallel to the door? The mathematical way we deal with a force and its location on an object is via the quantity called torque. Torque is a vector and is found by taking the "cross product" (a mathematical operation) of the position from a reference axis that the force is applied and the force itself. This is mathematically written as...

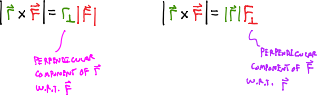

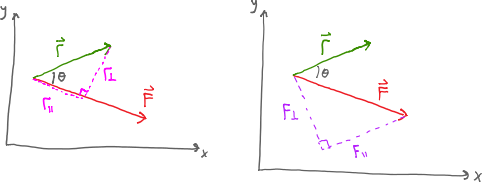

$\vec{\tau} = \vec{r} \times \vec{F}$

The magnitude of torque is...

$\left| \vec{\tau} \right| = \left| \vec{r} \right| \, \left| \vec{F} \right| sin(\theta)$

...where $\theta$ is the smallest angle between the position vector and the force vector when placed tail-to-tail. It is highly recommended that you construct a vector-operation diagram to determine the angle $\theta$.

The cross product is a mathematical operation that asks, "how perpendicular is one vector to the other?". Thus the magnitude of torque is often found in the following way...

Or a physical representation of the above two definitions looks like...

The vector nature of torque is beyond the scope of this class at the moment. However, we still need to define a rotational direction. The convention that we used in rotational kinematics is also used here. Counter-clock-wise (ccw) is positive and clock-wise (cw) is negative. The sign convention is added in by hand based on which direction the force would want the object to rotate around a chosen reference point.

Statics and dynamics

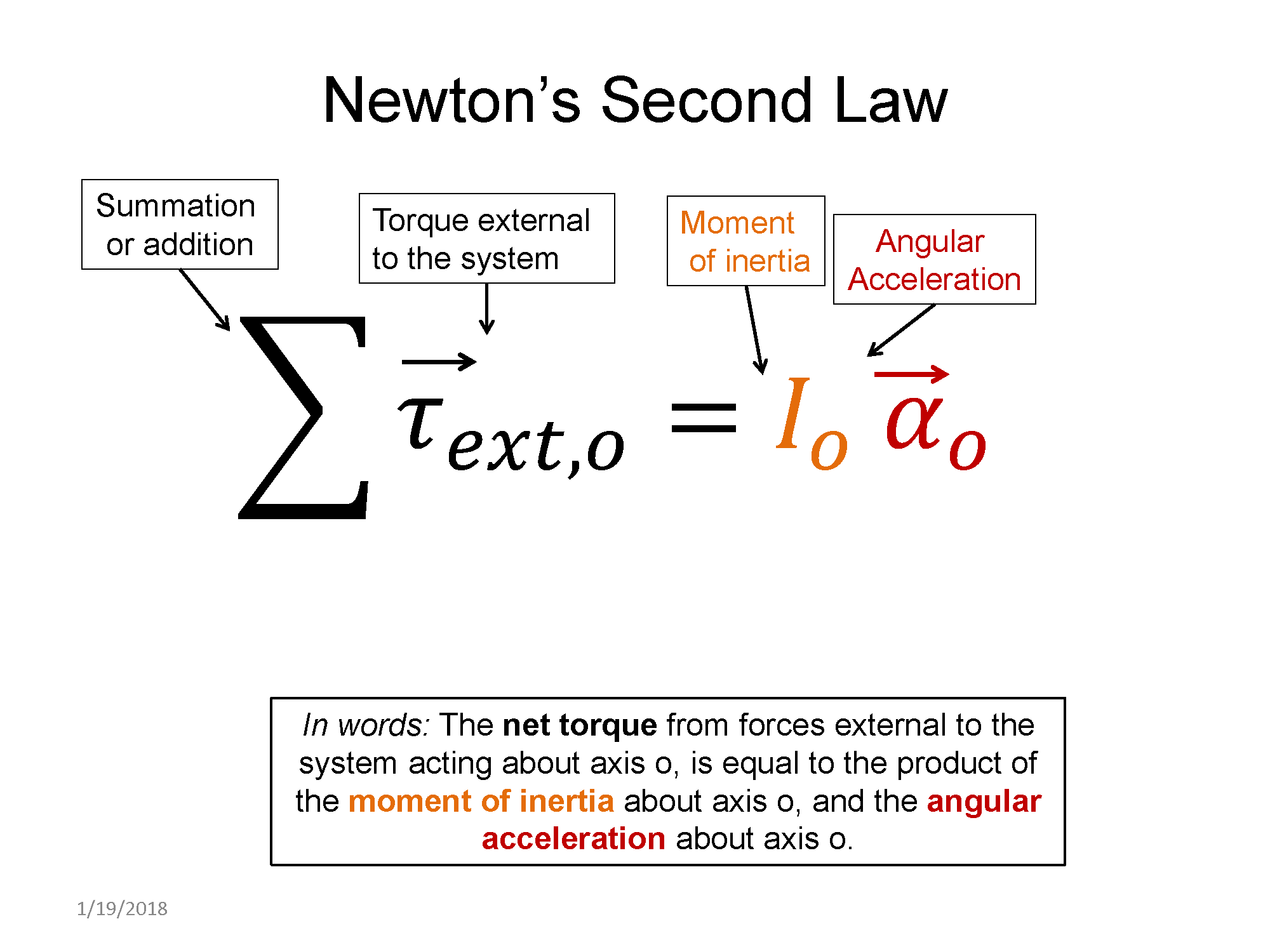

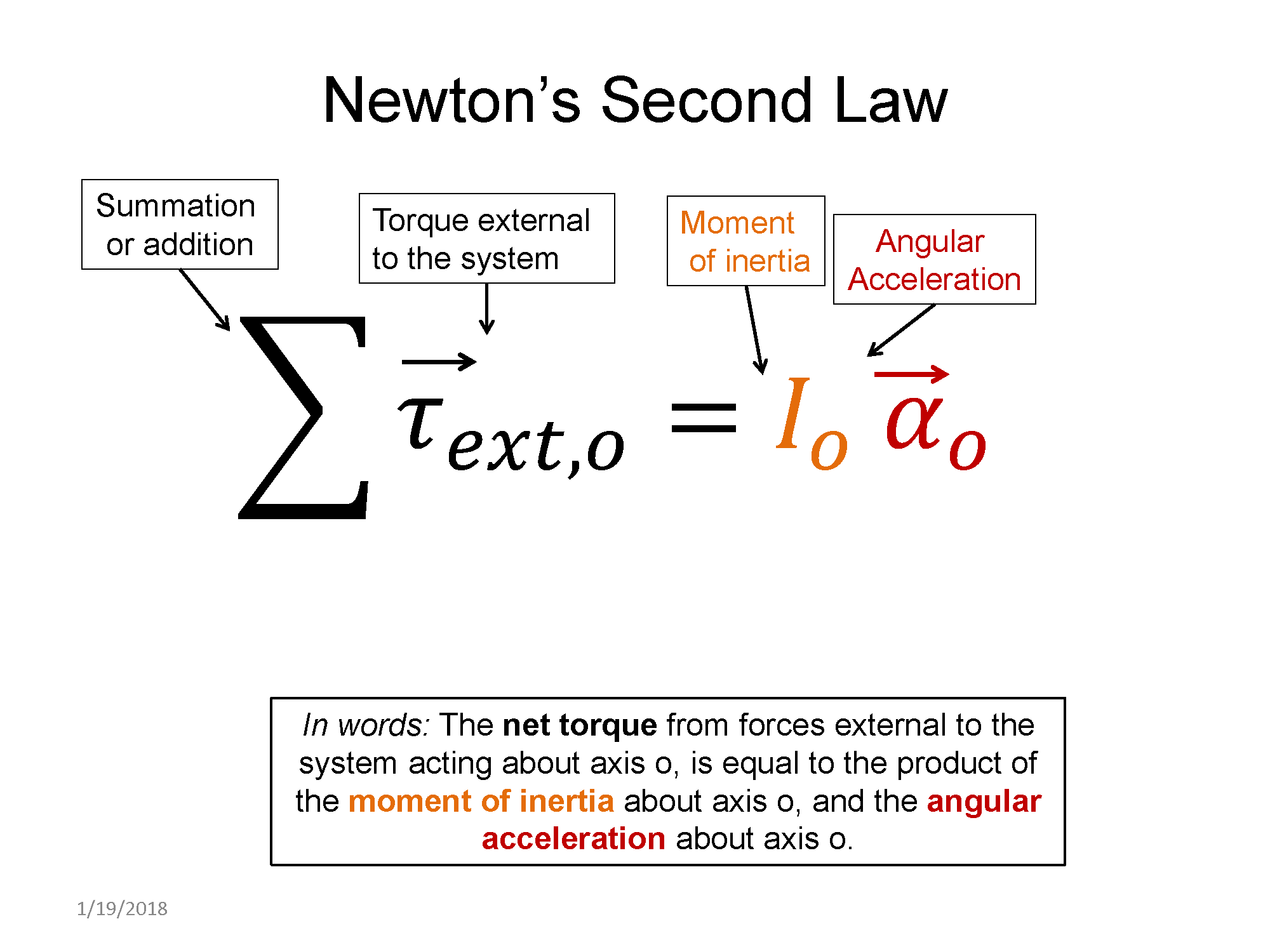

Now that we have defined a way to mathematically work with torque, let's revisit Newton's laws of motion as applied to the point particle model (linear motion) and also introduce its form in the rigid body model (rotational motion).

Statics and dynamics are terms used to describe the different scenarios that fall out of the two Newton's 2nd law equations above. The scenarios can be summarized by the table below. In this section we will focus mostly on the rotational portion since this is the newer topic being introduced.

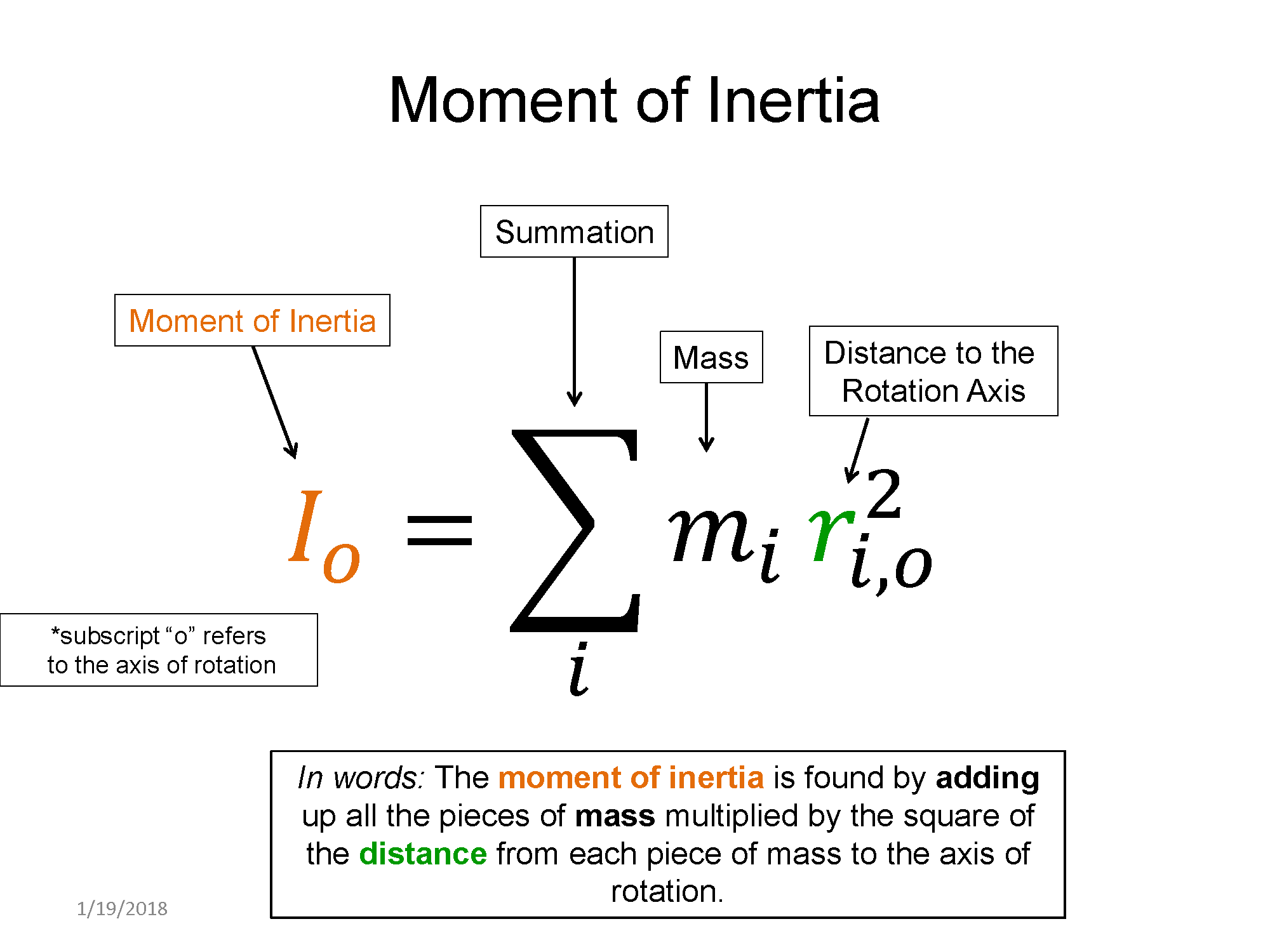

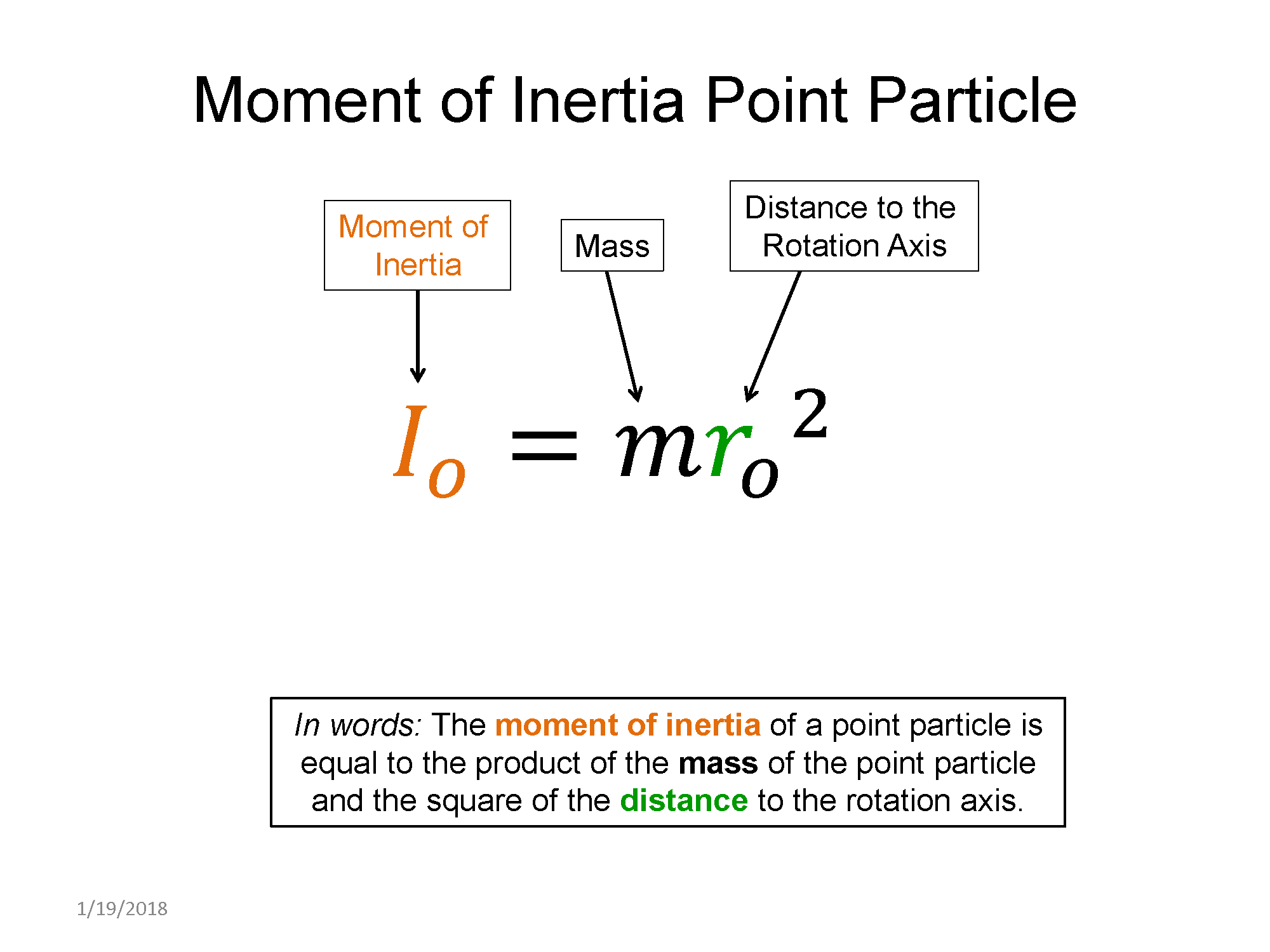

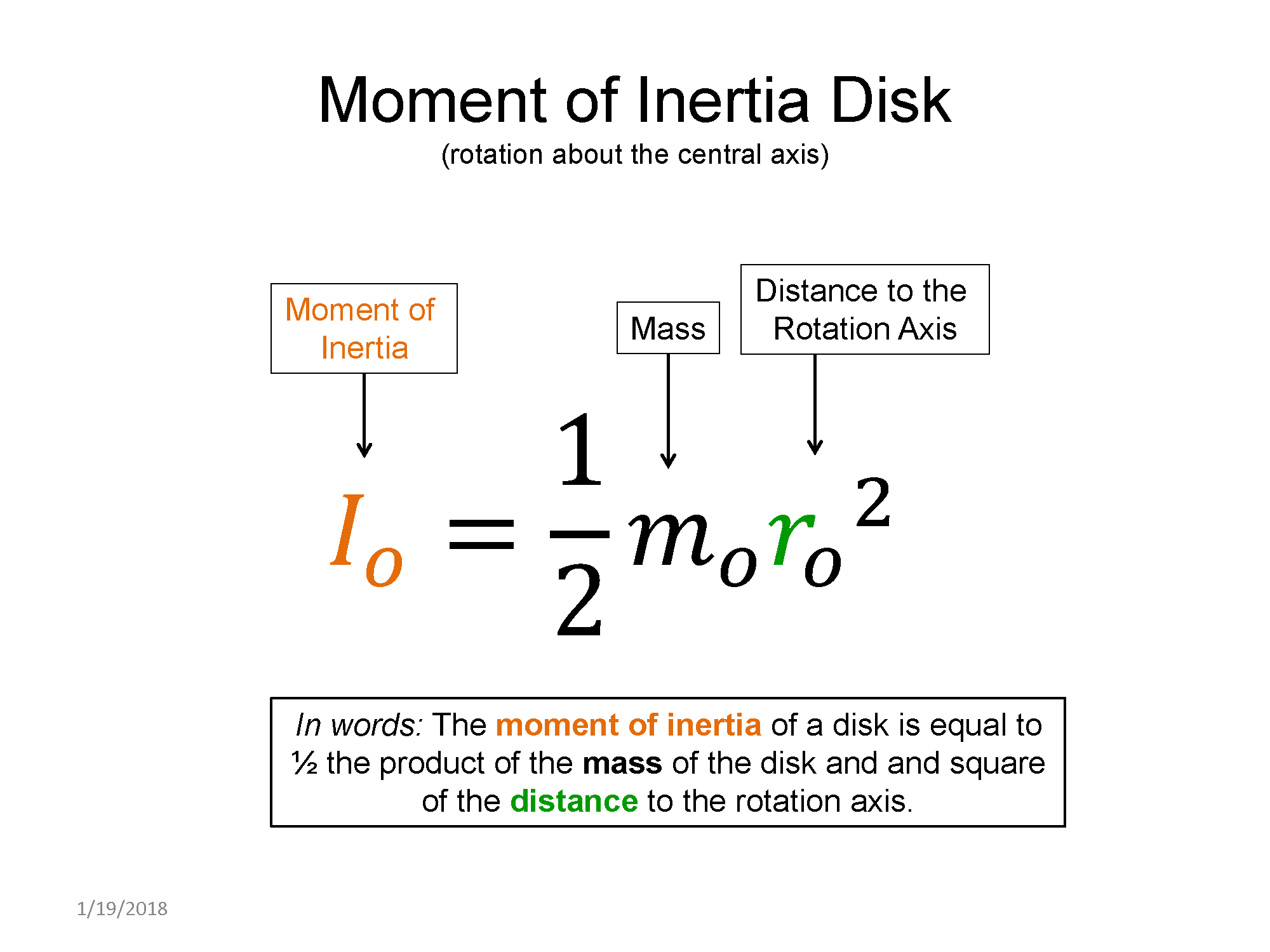

A new quantity shows up when dealing with rotational dynamics, moment of inertia $I_o$, where the subscribe "o" refers you to the axis of rotation. The moment of inertia is analogous to mass in the point particle model. The mass in the point particle model plays the role of inertia, which we can view in the following way: the larger the mass (i.e. the larger the inertia) the harder it is to increase the translation motion of an object. Think about a massive object on a frictionless surface, if you stand on a surface with friction and push the massive object, it is really hard to start to get moving at a high speed. If the object were much less massive, you would have no problem getting the object up to a fast speed. Now we can understand what role the moment of inertia plays in rotational motion. Just like mass, the larger the moment of inertia, the harder it is to increase the rotational motion of an object about an axis. Again, a simplified thought experiment goes something like this: if object that is not rotating has a large moment of inertia, it would require a lot of effort on your part to get it to start rotating at a fast angular speed. If the object has a much smaller moment of inertia, it would be much easier to get it rotating at a fast speed.

The moment of inertia depends on the axis of rotation and the way that the mass is distributed around this axis of rotation. For example, if you hold weights in our hands and stretch your arms out you would have a larger moment of inertia about the axis that runs from your feet to your head than you would if you held the weights tight to your body.

Key Equations and Infographics

Now, take a look at the pre-lecture reading and videos below.

BoxSand Videos

Required Videos

Rotational dynamics overview 2nd law(8min)

Rotational dynamics equilibrium(2min)

Rotational dynamics torque, cross product(10min)

Suggested Supplemental Videos

OpenStax Reading

OpenStax Section 9.1 | The First Condition for Equilibrium

OpenStax Section 9.2 | The Second Condition for Equilibrium

Fundamental examples

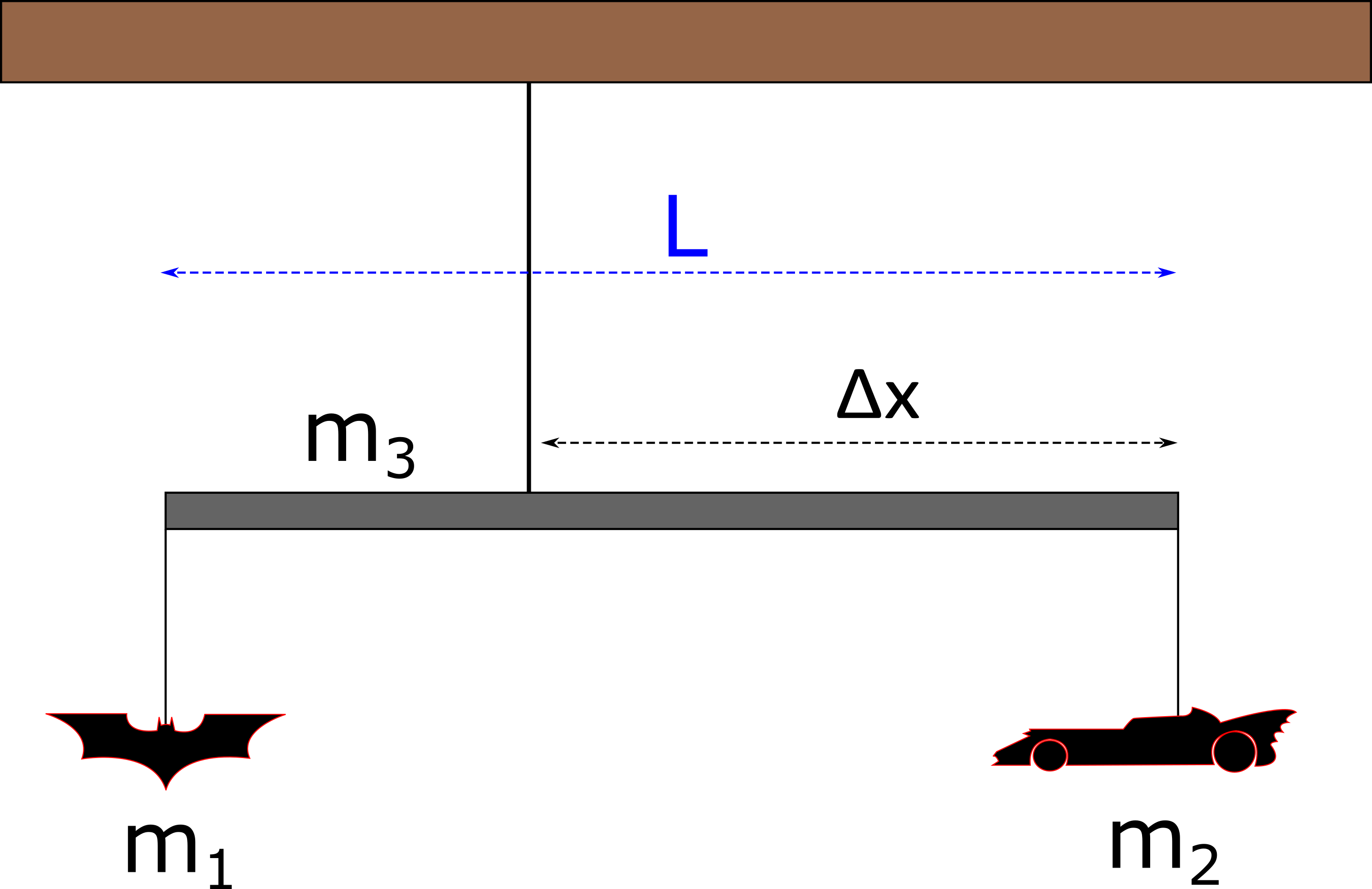

1. A very simple mobile that hangs from a ceiling can be constructed with a rigid rod of uniform density and length $L$, that has two plastic toys hung from the rod's ends as seen in the figure below. At what distance from the right side of the rod must you connect the string that attaches to the ceiling such that the system is in static equilibrium? Let $m_1 = 0.5 \, kg$ and $m_2 = 1.5 kg$.

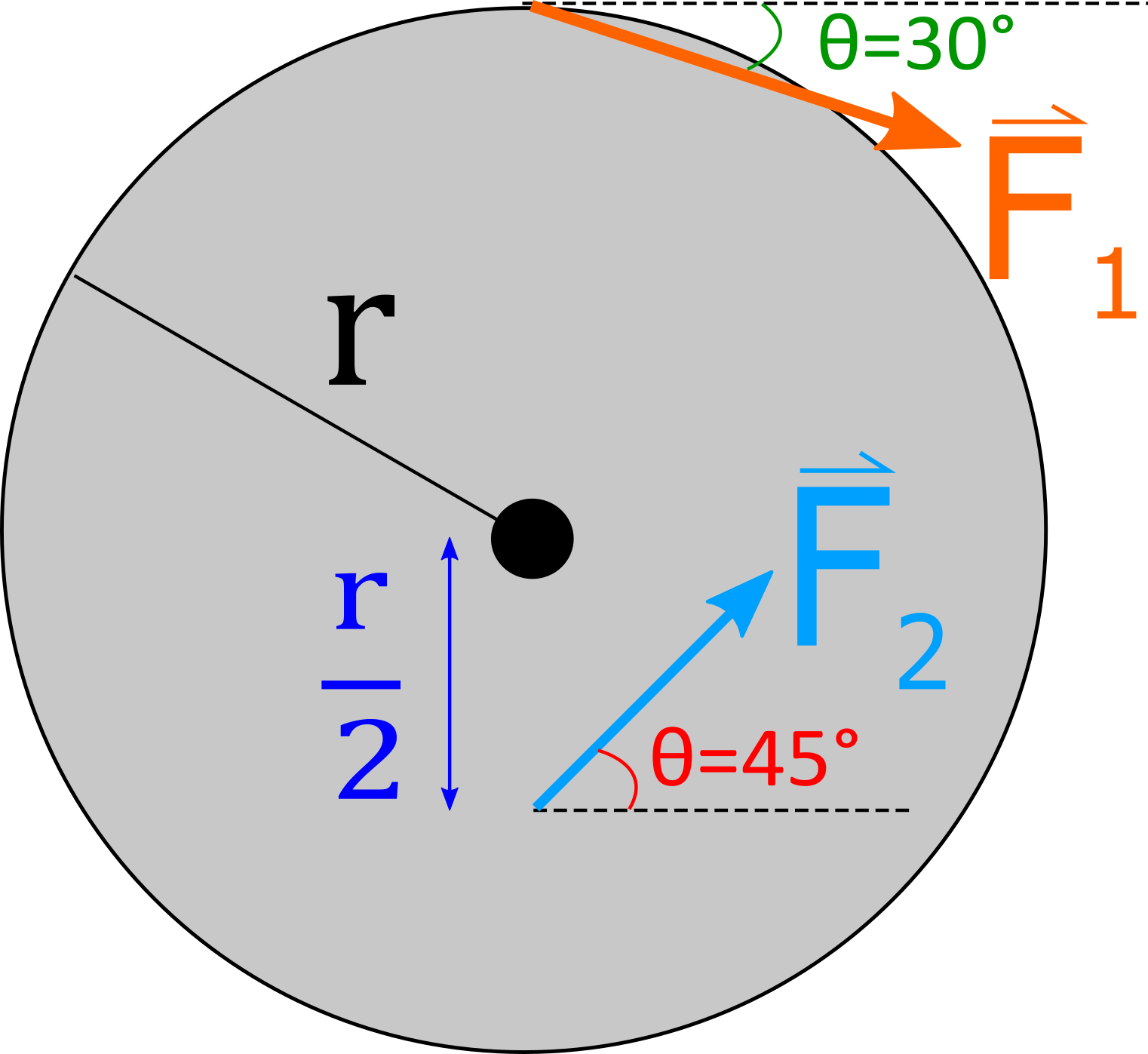

2. The figure below shows two forces acting on a $7 \, kg$ solid disk that is free to rotate about it's center and has a diameter of $d = 3 \, m$. What must the magnitude of $\vec{F}_2$ be such that the disk is in static equilibrium? The moment of inertia for a solid disk about it's center, perpendicular to the face of the disk, is $\frac{1}{2} m \, r^2$, where $r$ is the radius. Let $| \vec{F}_1|=10 \, N$.

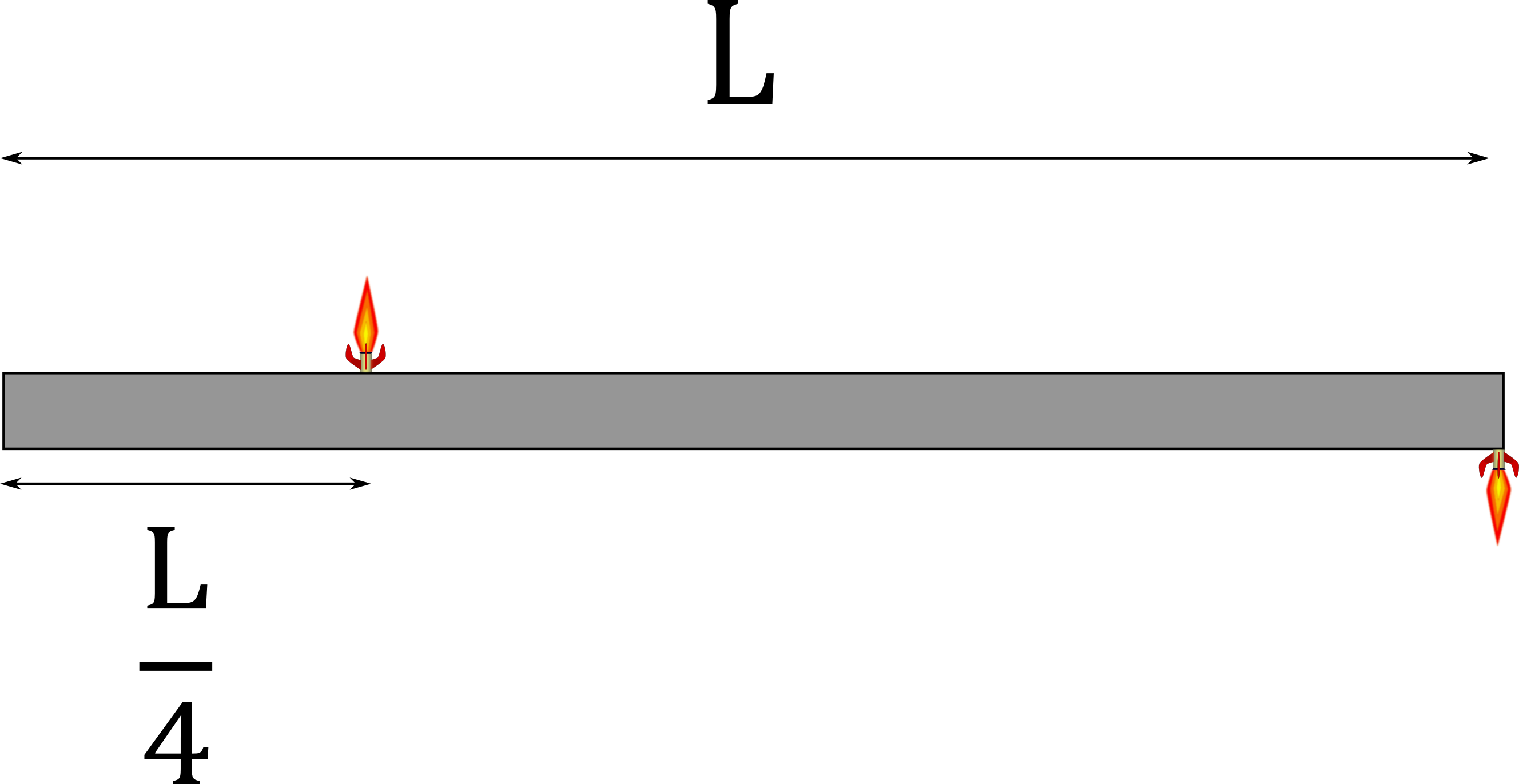

3. During the initial stages of building a Death Star, Tiaan Jerjerrod attached two very small rockets to a large quadanium steel beam with uniform density, located in deep space, as seen in the figure below. Both rockets provide a constant thrust of $500 \, N$. Tiaan wishes to rotate the beam by 90 degrees. The length of the beam is $L=60 \, m$. The beam's mass is $6.4 \times 10^{4} \, kg$, and the moment of inertia about the center of the beam is $\frac{1}{12} m \, L^2$.

(a) What is the angular acceleration of the beam?

(b) How long does it take to rotate the beam by $90^{\circ}$?

(extra) ... Just before the $90^{\circ}$ mark, do you need to turn off the thrusters to stop the rotation?

CLICK HERE for solutions.

Short foundation building questions, often used as clicker questions, can be found in the clicker questions repository for this subject.

Post-Lecture Study Resources

Use the supplemental resources below to support your post-lecture study.

Practice Problems

Recommended example practice problems

- set 1: Problems with solutions, Website Link

- set 2: Static net torque = 0, Website Link

- set 3: PDF of free body diagram problems, Offsite PDF Link

For additional practice problems and worked examples, visit the link below. If you've found example problems that you've used please help us out and submit them to the student contributed content section.

Additional Boxsand Study Resources

Additional BoxSand Study Resources

Learning Objectives

Summary

The objective is to analyze forces acting to cause or prevent rotation of a rigid body using the concepts of torque, which is an application of the cross-product, and Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation. Special emphasis is placed on connecting a net torque to a net force analysis, including concepts of center of mass and moment of inertia.

Atomistic Goals

Students will be able to...

- Identify and define the cross product as a vector operation and show that it increases as the vectors become more perpendicular.

- Differentiate between a dot product and a cross product.

- Define the magnitude of a cross product as the magnitude of the first vector times the magnitude of the second vector, times the sin of the smallest angle between the two, when placed tail to tail.

- Differentiate a reference axis from a coordinate system and an origin.

- Identify that a torque is a cross product between a position vector that points from the reference axis to the point where a force is applied and that applied force.

- (UPMF) Explain that a torque is a vector, yet we limit our study to forces in a plane, allowing the vector nature to be accounted for with a sign convention.

- Find the sign of the component of torque by determining if the force would make the object rotate clock-wise (cw) or counter clock-wise (ccw), with convention being that ccw is positive and cw is negative.

- (UPMF) Differentiate a point-particle and rigid body analysis.

- Explain Newton's 2nd law for both point particles and rigid bodies and compare and contrast the two.

- Identify the axis a system would rotate about if allowed to evolve.

- Choose a reference axis that simplifies the mathematical representation of Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation.

- Draw an extended free-body diagram (eFBD) which includes a representation of the shape of the rigid body, the force vectors where they act on the body, and position vectors pointing from the reference axis to the force locations.

- Draw a vector operational physical representation for every force and its associated position vector by placing them tail-to-tail.

- Use the vector operation diagram for a cross product to determine (1) what the smallest angle between the force and position vector is and (2) whether the torque is relatively large or small.

- Define the moment of inertia and determine its magnitude based on the distribution of mass relative to the reference axis.

- Add multiple moments of inertia to determine the net moment of inertia for multiple objects about a reference axis.

- Differentiate between static and dynamic equilibrium for both rotational and translational mechanics.

- Apply Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation of rigid static bodies.

- Apply Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation of rigid dynamic bodies.

- Connect rotational kinematics and mechanics via the angular acceleration.

- Simultaneously apply a translational and rotational Newton's 2nd Law analysis to a system.

- Analyze a system including a frictionless massive pulley.

- Estimate the center of mass for an object or a system of multiple objects.

- Calculate the center of mass for a system of multiple objects where their individual center of mass is known.

- Demonstrate that an unconstrained system rotates about its center of mass.

- (UPMF) Show that for an unconstrained object under the influence of gravity, the object will tip over if the center of mass is horizontally beyond the outermost vertical normal force.

YouTube Videos

Crash Course Physics does a great job of introducing torque with everday examples.

Pre-Med Academy introduces torque.

Bozeman Science covers statics.

Khan Academy explains how to find torque for angled forces.

Moment of inertia explanation. At 12:25 doc begins to derive moments of inertia for various objects, you can ignore this.

Doc Schuster talks about rotational dynamics.

Simulations

PhET simulation on dynamic torque. Note that when you let the wheel rotate without acceleration, it is actually in torsional equilibrium despite the fact that it is in motion.

For additional simulations on this subject, visit the simulations repository.

You need to have Java installed and updated. Download and run the file.

Demos

History

Oh no, we haven't been able to write up a history overview for this topic. If you'd like to contribute, contact the director of BoxSand, KC Walsh (walshke@oregonstate.edu).

Physics Fun

Proper lifting technique to minimize the torque on your back by minimizing the moment arm.

https://media.oregonstate.edu/media/t/0_rrr2h2ii

Check out a tower of lire and how it relates to statics

Other Resources

Read pages 1-10 for static equilibrium.

This links to a set of slides detailing static equilibrium.

Other Resources

This link will take you to the repository of other content related resources.

Resource Repository

This link will take you to the repository of other content related resources.

Problem Solving Guide

Use the Tips and Tricks below to support your post-lecture study.

Assumptions

Recognizing the physical situation by what time of equilibrium it is in (if any) is an important conceptual set to solving most problems with Newton's 2nd Law for Rotation. Translational equilibrium means that the system's sum of forces is equal to 0, meaning $a=0$. Dynamic translational equilibium means $a=0$, but velocity is non-zero, meaning the object is moving through space at a constant non-zero velocity! Static translational equilibrium means $a=0$ AND $v=0$, indicating our object is stationary in space (but this distinction has NO barring on if the object is rotating or not).

If an object is in rotational equilibrium, it has 0 net torques on the system (but could have multiple torques that cancel out), and this means $\alpha=0$, but there are two types of rotational equlibirum. Dynamic rotational equilibium means $\alpha=0$, but angular velocity ($\omega$) is non-zero, meaning our object is rotating at a constant angular velocity but not speeding up or slowing down in its speed of rotation. Static rotational equilibrium means $\alpha=0$ AND $\omega=0$, this indicates an onject that is not rotating. Again, rotational equilibrium conditions do not effect translational equilibrium conditions, they are entirely separate.

For instance, an object in static translational equilibrium and dynamic rotational equilibrium is standing still in space, but rotating at a constant non-zero velocity. An object in dynamic rotational AND dynamic translational equilibirum is moving at a constant velocity through space AND rotating at a constant angular velocity. Both these objects are not accelerating linearly or rotationally because they are both in some type of equilibirum for both translation or rotation, so in either case, we are free to set the sum of all forces and the sum of a torques equal to 0, as an assumption!

Checklist

- Read and re-read the whole problem carefully.

- Visualize the scenario. Mentally try to understand what the rigid body is doing and what forces are acting on it along with the location of the forces on the body.

- Draw a physical representation of the scenario, this may include a FBD and/or an e-FBD.

- Draw all forces acting on the object at the known locations. (Helpful hint: Draw a FBD first. All the forces on the FBD will show up on the e-FBD, no more, no less.)

- Define a coordinate system on your e-FBD. Conventional coordinate system is ccw(+) and cw(-).

- Label a location that represents the axis that you would sum torques around. The location of this axis can be placed anywhere, but defining it to be at the location of unknown forces is a good way to eliminate the torque due to the unknown force.

- Specify the moment arms for all forces acting on the e-FBD.

- Identify all the known and unknown terms.

- Use Newton's rotational version of the second law and sum the torques around the axis you chose.

- Identify if the object is in rotational equilibrium or not to determine the value of the angular acceleration.

- If the angular acceleration is not zero, determine the moment of inertia of the object around the axis you chose.

- Determine the number of unknowns from your rotational version of Newton's second law equation. If more than 1, perhaps choose a different axis to sum the torques around, or draw a regular FBD to build more equations.

- Carry out the algebraic process of solving the equation(s).

- Evaluate your answer, make sure the units are correct and the results are within reason.

Misconceptions & Mistakes

- The axis you choose to sum the torques around does not have to be the actual pivot point that the object would rotate around.

- When calculating torque, do not forget to add a positive or negative based off of the direction that the force wants to rotate the rigid body about the axis you chose.

- An object does not have a single moment of inertia. The moment of inertia depends on the axis that the object would rotate around. Thus objects can have many moments of inertia for different axes.

- Torque has the same dimensions of energy, but torque is not a form of energy. Torque is a vector, and energy is a scalar

Pro Tips

- For any force that is not parallel or perpendicular to the moment arm, take the time to draw a vector operation to determine the correct angle between the force and moment arm.

- If you are having troubles identifying forces for an e-FBD, draw a regular FBD first. The same forces that show up on a regular FBD for an object show up on an e-FBD for the same object. In addition, often-times using both a translation analysis and a rotational analysis together will help expedite the process of solving the problem.

- Identify all the known and unknown forces on your e-FBD before you define an axis to sum the torques around. Once you know which forces are unknowns, try defining your axis through the location of the unknown forces to eliminate the unknown force in the final equation derived from summing the torques.

- If there is a torque which an unknown direction, just guess the direction and apply the rotational analysis of summing the torques. For example, if you guess a torque to be ccw(+), and you get a negative number for the value of that torque, then you define the direction incorrectly initially, if the value was positive, then you guess correctly (assuming no algebraic mistakes).

- Scaling forces and distance on an e-FBD can help you visualize the contribution of each torque from each force. When finished solving the problem, you can then go back to your scaled drawling to see if the answer is what you were expecting.

Multiple Representations

Multiple Representations is the concept that a physical phenomena can be expressed in different ways.

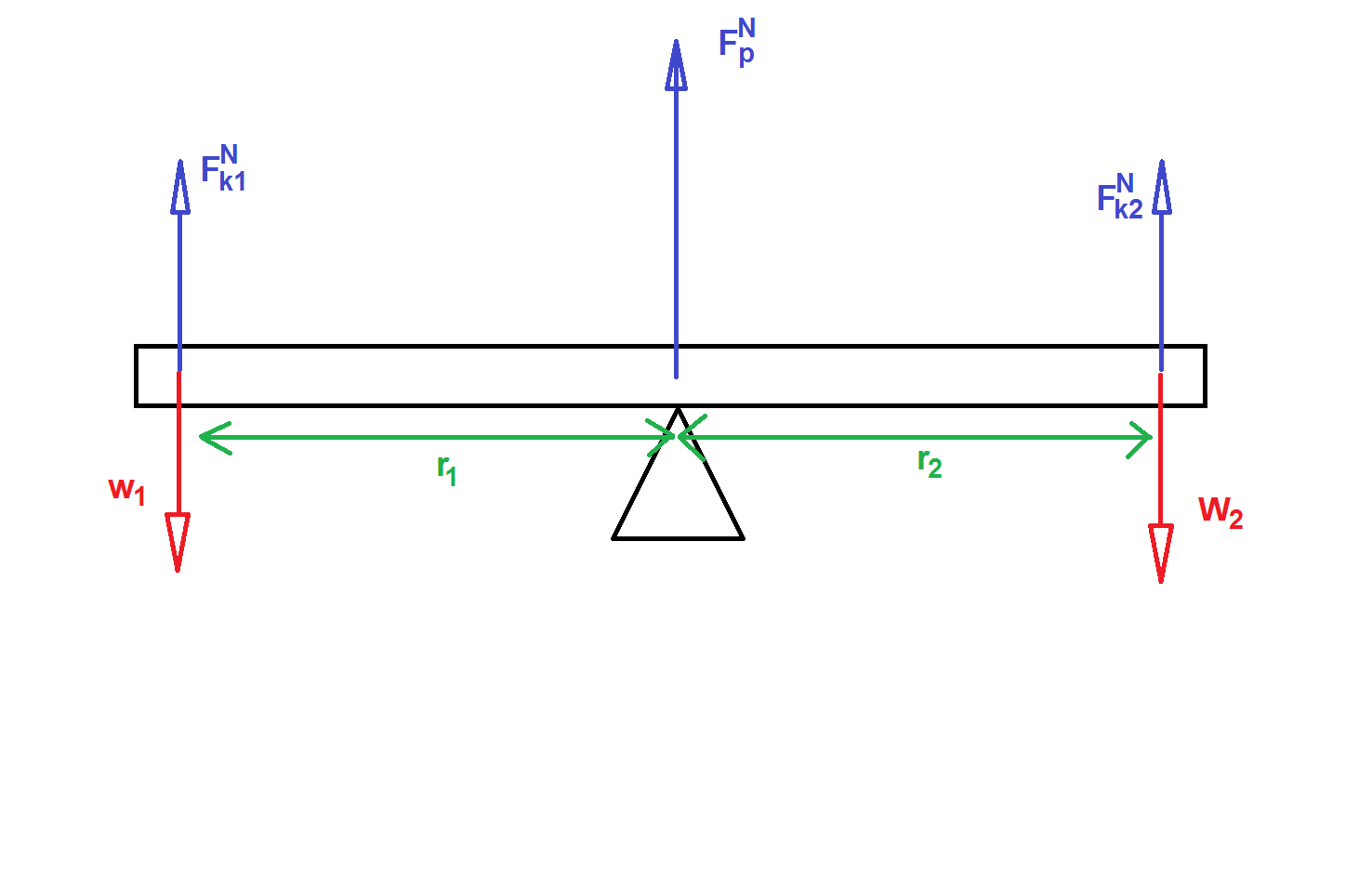

Physical

We represent the system with an extended free body diagram which places the forces at locations, lets consider two kids on a seesaw.

Naturally your not expected to draw something as complex as the above, you should draw something like the following.

Mathematical

Forces acting on an object can cause torque about some given axis. Torque ($\tau$) is defined as a cross product between force and displacement.

$\tau = r \times F$, r is the displacement vector from the axis of interest to the location the force is applied.

Remember to take geometry into account when calculating torque! Only the force component perpendicular to $r$ contributes to the torque.

$|\tau| = |r| |F| \sin \theta$

With regards to our seesaw scenario, the net torque of the see saw about its pivot axis is,

$\sum \tau = r_1 \times F^{N}_1+r_2 \times F^{N}_2$

If $\tau_{net} = 0$, then we say that the system is in rotational equilibrium.

The net torque and moment of inertia about a chosen axis tells us something about the angular acceleration of that body about that same axis.

$\alpha = \frac{\sum \tau}{I}$

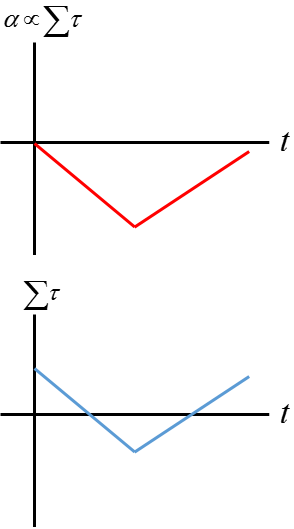

Graphical

Rotational acceleration is proportional to the net sum of all the torque.

Descriptive

Two children sit on a seesaw. Child 1 sits a distance of $r_1$ from the pivot. On the other side, child 2 sits a distance of $r_2$ from the pivot.

Experimental

Find a straight long flat piece of wood like the one in the figure below. Next, grab some objects to place on the piece of wood. Now, place the piece of wood on top of a fulcrum and add arrange some objects on it so that the piece of wood balances on the fulcrum. You can vary the position of the wood and try placing the objects in a new arrangement to see where they need to go in order to find the equilibrium.